Open Letter

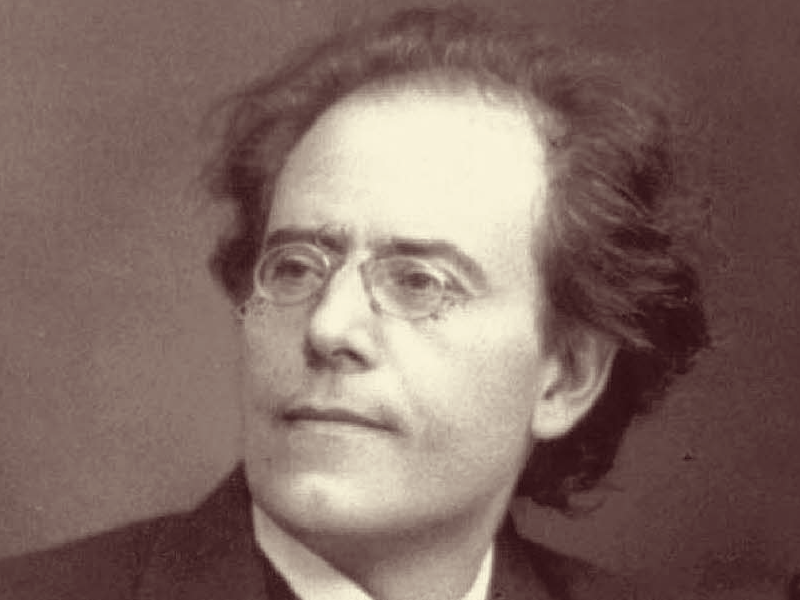

Before dying, Gustav Mahler would have said these few words: “My dear little Mozart!”. Such words testify to his great love for simplicity up to his last breath. This simplicity that, these days, is deliberately mistaken for easiness or triviality, by the same who lack of it; this simplicity long gone, enemy of an elite who pretends to find intelligence only in complexity and esotericism. In this world of excess and abundance, simplicity has become an abuse, a rude word; it’s aggravating, it’s upsetting, it’s irritating for our civilization.

In music, thus, detail prevails over the whole. The search for sound effect is at the height of subtlety. No place left for speech; no place left for the musical sentence; no place left for melody. This melody, long abandoned too, that means — in the eyes of the elite nobody dares to overthrow — nothing but vulgarity and mediocrity, dismissing the craftsmen of a new universal musical order as uneducated and ignoramus.

And that’s where the question lies. Isn’t it the function of the artist to speak to the ignorant? Indeed, the true artist lives on a higher level than the rest of the world; but he is still a man nonetheless. A man who has to lead his brothers toward higher peaks. A man who has to build a bridge between two shores, able to find a path between shadow and light. A man, a true creator: an Artist.

Devoid of all humility, being more scholarly than wise, the modern artist no longer sees himself as a link between two worlds: the artist presents himself as the supreme tower, the unreachable peak; he becomes even more important than his whole work. So lower down to this world of ignoramus, no way! The artist prefers staying on his rock jeering at the world, sniggering from the top of his knowledge that, by his own isolation, becomes as trifling as it becomes ridiculous. And if he considers he doesn’t need other people, they learn to do without him. He who no longer wishes to delight the soul and heart of his fellowmen. He who no longer holds out a hand to anyone; he who he is no longer an artist then. He who no longer cares for humankind although he would have us believe he could have been its master.

Today, science and technology are the only guarantees for quality, even for a work of art. When the ability of the craftsman should fade behind the beauty of the work and leave room only to pure emotion, the conception and the creation process now take precedence over the emotion that the piece of work should create. The masterpiece is no longer beautiful: it is interesting! And its appreciation comes from its explanation which takes the place of all its expression. By its explanation, does the work make up for the weakness of its own speech? We comment upon, we quibble about the matter, as if creation no longer was able to explain itself, as if it stammered, as if it had turned voiceless or, even worse, dumb.

Explanation of a work of art is negation of its own existence. Nothing but the piece of work can raise the mind of its spectator; it is the work itself that must give him the keys to its own understanding, the keys it holds tightly inside, so that no go-between — as scholar as he could be — can interfere between creation and the person who receives it, and so that no one dares disturb this frail intimacy; the work of art as the unique link between creator and spectator. The work of art: a hyphen between men, the sign for a new era of hope and brotherhood.

Musicians, my friends, keep our critical mind and our immoderate taste for beauty. Be curious, remain uncompromising and dare get inspired by these few lines from Hector Berlioz: “Not even the authority of a hundred old men, not even if they were all 120 years old, would make us regard fair as foul or foul as fair.”

And now, it’s our turn to invent “the classical music of today”!