Legacy & Influences

Be of our time without forgetting the past ...

The Masters of the past cannot be only models. They teach us. They inspire us. They show us the way and shine with their exemplarity.

Beethoven, Schubert, Bellini, Chopin, Liszt, Wagner, Verdi, Franck, Brahms, Saint-Saëns, Bizet, Moussorgski, Tchaïkovski, Dvořák, Grieg, Rimski-Korsakov, Fauré, Mahler, Debussy, Dukas, Sibelius, Ravel, Stravinsky, Prokofiev, Gershwin, Shostakovich, Bernstein and many others are for me fathers — and I dare believe that one day you will be able to say peers — who gave me a taste for emotion , the desire to transmit it, and this insatiable thirst — certainly pretentious but no less sincere — to always want to offer something to the world!

Closer to us, other great musicians are always a great source of inspiration for me: Duke Ellington, Django Reinhardt, Stéphane Grappelli, Dave Brubeck, Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Michel Petrucciani, Stefano Di Battista and Elmer Bernstein, Ennio Morricone, John Williams, Vladimir Cosma, Dany Elfman...

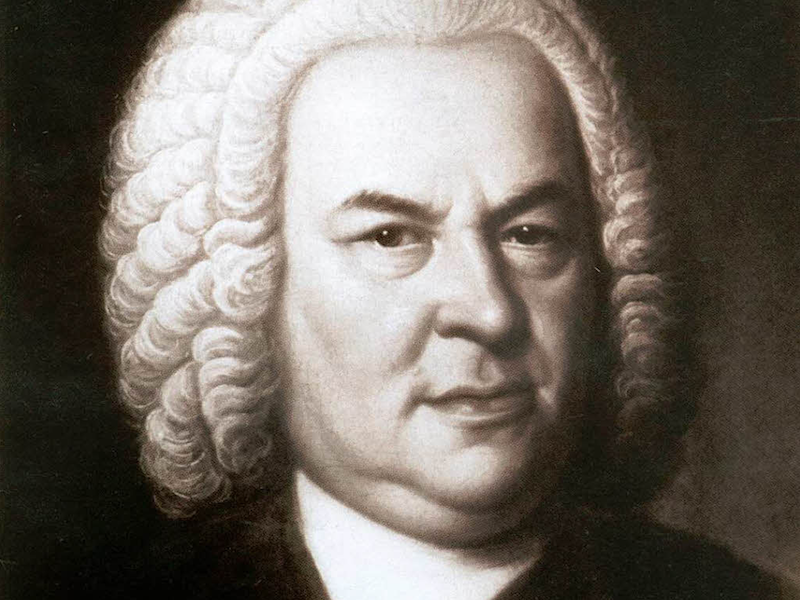

Finally, and above all, the two composers most dear to my heart remain Bach and Mozart, with a very particular affinity for the latter.

Prenez un modèle, imitez-le. Si vous n’avez rien à dire vous n’aurez rien de mieux à faire que de copier. Si vous avez quelque chose à dire votre personnalité ne paraîtra jamais mieux que dans votre inconsciente infidélité.

... and its two great Masters!

This is what has always fascinated me in the work of Johann Sebastian Bach, it is this little stream of a few notes, which, measure after measure, becomes a stream , then river and, carting everything in its path, floods the valley of our souls with great contrapuntal floods, until the final apotheosis where a river of notes flows into the vastness. This could be the definition of a fugue by Bach.

What gives Bach this true status of Father of Western music, like a colossus on his pedestal, it is this boundless imagination which allows him to transform the slightest note of water into an ocean of music. This unique strength of being able to go from nothing to everything, while looking like nothing.

Yes, Bach is Music. All the Music. What would there be in the work of any composer - and even Schönberg or Stravinsky - that there was not already in the work of Bach?

Bach is also — and perhaps above all — the love of God. His music is a constant translation of Genesis: “Let there be light. And the light was”. Bach never ceases to put these words to music, to translate the notes into expressions of this gushing, relentless and divine force, and manages to create in us this feeling of going beyond our own human condition, this strong and absolute feeling of the ineffable and the unexplained. With him, the beautiful, the true, the divine, is very close, accessible, finally at hand. He constantly promises us this beyond. He asserts it to us as a counterpoint. Doubt is no longer allowed: with him, we are there!

But God — when he exists! — always sends his son to earth. If we need a father, we also need a brother. And if the Cantor of Leipzig remains the undisputed master of writing and counterpoint, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart is — for me — the genius of form; the master of balanced and coherent structure, always articulating around what he knows how to do best, which is his own and innate: melody, song and grace. All of Mozart’s music is just song. Mozart is also opera, drama and theater. In this sense, what composer more dramatic than him? And it is precisely this taste for drama that enables him to excel in mastering the sonata form; because what is the sonata form if not the setting to music of a drama where the flesh characters are the melodies of the spirit. What always amazes me most about Mozart is this extraordinary ability to conceive the work as a whole; this ability to build a building that you have to look at from afar to appreciate all its grandeur.

If it is true that Beethoven will give in more than once to his whims and will shamelessly interrupt the musical discourse, Mozart, meanwhile — child of the century of Enlightenment, not of Bonapartism —, and despite his genius, will never allow himself to dictate to Music. Notes after notes, he will remain his humble servant. And in his quest for universality, he will put all his art at the service of clarity and simplicity. And unlike his master friend Haydn who, by his music, always takes us where he wants and not where we expected him, Mozart, while going exactly where he wants, takes us by the hand and gives us the feeling that we are where we always dreamed of being! As if the music flowed naturally; as if the music was obvious. As if his music had always been in us.

Finally, how can we not admire his particular way — which is often lacking in Beethoven, less in Schubert — of his writing serious music without ever taking yourself seriously; by telling us about ourselves and our serious times, but with such lightness. Mozart, this lover of men and humanity.